From Ashes to Riches: Indonesian Communities Profit from Peatland Agriculture

---

LIMBUNG AND JONGKAT, WEST KALIMANTAN – A school building saved from burning down; farmers with 50% higher income; a healthier peatland with much reduced greenhouse gas emissions: these are just some of the results of a multifaceted initiative by Indonesia’s Peat and Mangrove Restoration Agency (BRGM), with support from the United Nations Office for Project Services.

Since its launch in 2019, the agency’s progamme, which includes training for villagers and critical infrastructure upgrades, has dramatically reduced fire risk and equipped the residents of 121 villages in coastal West Kalimantan with new skills and resources to uplift their communities.

A school building saved from burning down; farmers with 50 per cent higher income; a healthier peatland with much reduced greenhouse gas emissions: these are just some of the results of the multifaceted initiative.

Since its launch in 2019, the programme, which includes training for villagers and critical infrastructure upgrades, has dramatically reduced fire risk and equipped the residents of 121 villages in coastal West Kalimantan with new skills and resources to benefit their communities.

Farming without burning

“We learned how to work the land without burning the bush and crop residues – and in the meantime found ways to grow crops we can sell for more,” said Suprapto, a farmer in the village of Limbung, just south of the Pontianak, the provincial capital.

“The training we received made everything so simple,” said Sumi, a farmer and head of the women farmers group in Jongkat. “Thanks to the market research by BRGM and its partners, we also learned which are the crops we should be growing for cash.”

Limbung and Jongkat are on peatland, wetlands whose soil consists almost entirely of organic matter derived from the remains of dead and decaying plant material. Under certain geological conditions, peat eventually turns into coal.

And like coal seams, peatland stores enormous quantities of carbon–dioxide—until it alights. Fires do not only devastate villages and farmers’ livelihoods, but they also release a substantial amount of carbon-dioxide.

Burning bush to clear land and plant residues after harvest, led to 245 fires in the district around Limbung in 2021 – a staggering number given that a 2009 government decree forbade farmers from burning on peatland. “But without knowing any other methods to farm, we had no other options,” Suprapto explains.

Restored peatland

Increasing farmers’ options has had a profound impact, helping to reduce the number of fires that broke out last year to just 21. But that’s still 21 too many, says Jany Tri Raherjo, who is charge of BRGM’s operations in Kalimantan and Papua: “We need to reach zero fires – and fully restore peatland.”

Thanks to BRGM’s interventions, much of the peatland around Limbung is moist again – enabling farmers to grow vegetables such as cucumber, tomatoes, chili and eggplants.

“Horticulture really pays off,” Suprapto said. “The income of the villagers that are part of the programme is up by half.”

The additional income, Suprapto said, has in just one year helped families renovate their houses, buy new motorbikes and finance their children’s education.

In Jongkat, BRGM and an NGO engaged by UNOPS as part of a project funded by the Government of Norway, helped local farmers identify which crops are best suited to their land and to non-burn farming.

Around 20 families received training on non-burn agriculture and on the use of natural fertilizer, and are now showing the methods to their friends and families in other communities. “There is a joke that it is good to marry someone from Jongkat, because you then learn more profitable ways of farming,” Sumi says with a grin.

Blocking canals, retaining water

Training villagers in non-burn farming methods is crucial to making West Kalimantan’s coastal villages more sustainable. Equally important is upgrading irrigation infrastructure to keep rainwater in peatlands.

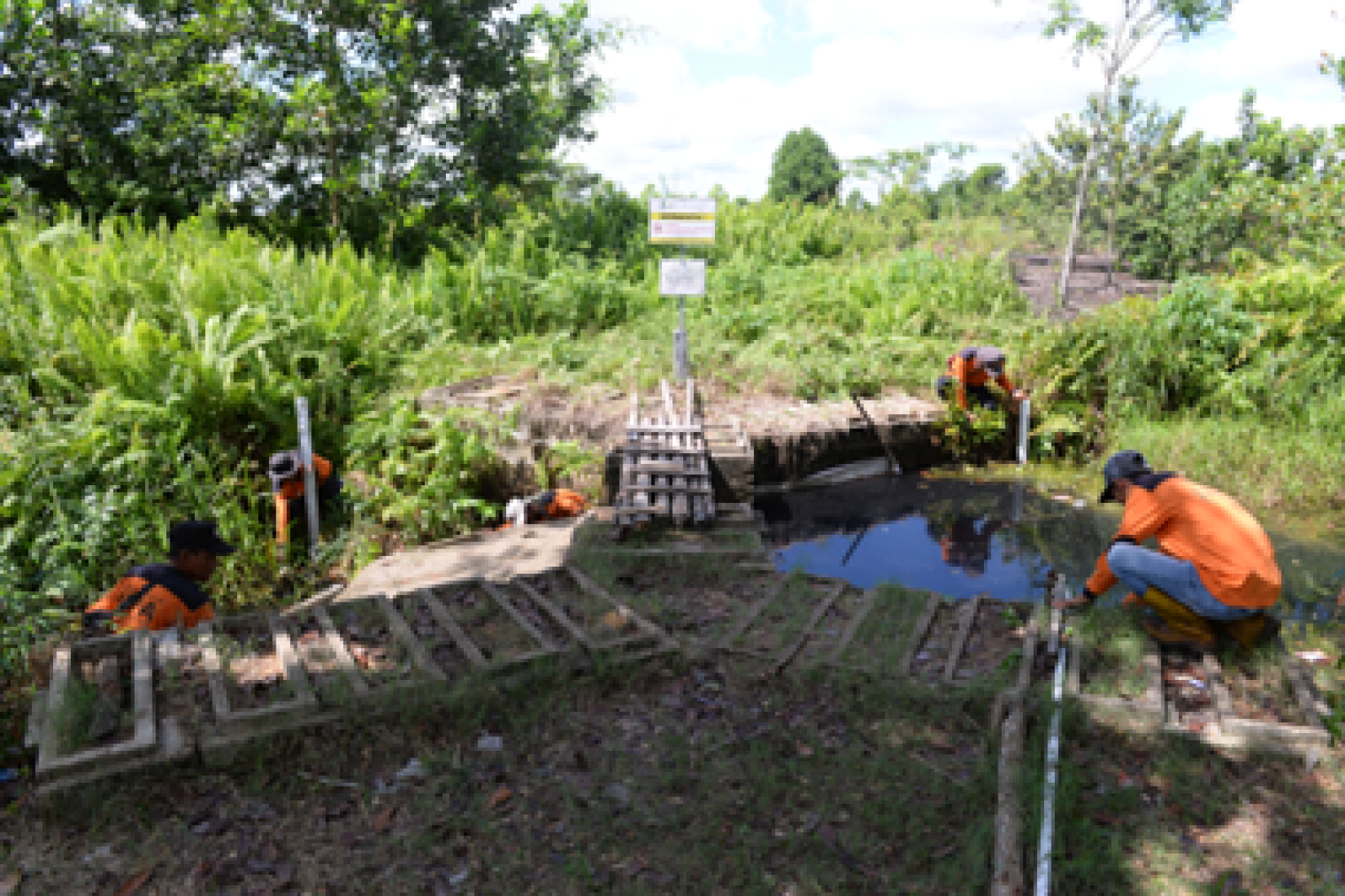

UNOPS provided design and financing for the construction of a few pilot canal blockers – concrete structures that keep the water in the canals that criss-cross the area, making water available year-round for firefighting and watering crops as well as wild peatland. Better irrigation prevents the land from cracking, drying out and decaying, thereby reducing the amount of carbon-dioxide released into the atmosphere. Peatland restoration also involves re-vegetation of the area, which in turn keeps the soil moist and decreases the chances of fires and decomposition.

When a 2021 peatland fire threatened a school building in Limbung village, volunteer firefighters trained by BRGM extinguished it using water from the pond created by a canal blocker and saved the school. “A few years ago, when the canals were regularly empty during dry seasons, we could not have done that,” said Trisno Slamet head of the community peatland management unit. Watering the land regularly and keeping the soil moist means that when fires break out only the vegetation above the peatland burns, not the carbon-rich land itself, BRGM’s Raharjo adds.

BRGM and its partners have built 179 canal blockers in 27 villages in the area – financed by the government and using a design based on the initial UNOPS model. “Knowhow from the UN was a great launchpad – we have adapted it to local conditions and improved the designs year after year,” Raharjo said. “We are now rolling out canal blockers that cost about half as much to build as the original.”

BRGM, with the support of UNOPS, the Ministry of Forestry and other players, has carried out restoration projects in 852 villages in Kalimantan, Papua and Sumatra. But thousands more remain. “The results are good, but not enough,” Raharjo says.

Key to their success at every stage, is community involvement, said Akira Moreto, acting Country Manager at UNOPS Indonesia: “Policing fires is hard; giving the community a stake in non-burn agriculture is a much more successful way of protecting peatlands and fighting climate change while improving livelihoods. This requires long term commitment from all sides.”

This article was originally published by the United Nations that can be found through this link: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/08/1139402