Special Needs Students Gain Confidence and More Agency Over Their Bodies

-----

The joy of the five students in teacher Reni Gusnaeni’s morning class is palpable. As the catchy piano refrain kicks in, Nabila, a 14-year-old with Down Syndrome reaches for the microphone as 13-year-old Kanza rises from her chair. They are joined by 15-year-old autistic students Lazuardi and Cici, and then by Jenar, a 17-year-old with an intellectual disability who pushes her white-framed glasses up her nose and begins to sway to the beat.

“I am a child with a healthy body, going through puberty,” the students sing in Indonesian, for what will not be the last time that morning. Accompanying the song’s opening line is a self-referential gesture that brings the students’ fingertips to their shoulders and then one of power that has fists clenched at temples. As the jingle continues, more gestures follow: palms are placed over hearts, then arms clasped around chests in a tight embrace.

Teaching young people about sexual health, the physical and emotional changes that come with puberty, and consensual and non-consensual touch can be a challenge in cultures where many consider sex-related subjects to be taboo. The cultural obstacles are often greater still when it comes to teaching young people with intellectual disabilities. But Ms. Gusnaeni and special needs educators in nine other Indonesian provinces are pioneering a learning approach designed to give young people a better understanding of their sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights, and with it, more confidence and autonomy. Her puberty song is part of a series of educational tools inspired by a training course the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) designed jointly with Indonesia’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, and Ministry of Health. Those tools, she says, have helped the 27 students at SLB-C Plus Asih Manunggal, a private special needs school in Bandung, set bodily boundaries and become more assertive in guarding them.

“Now they can say no to people who want to touch them, even when they’re playing,” Ms Gusnaeni says. “They are also more confident to set their private space, for example, when they go to the bathroom.”

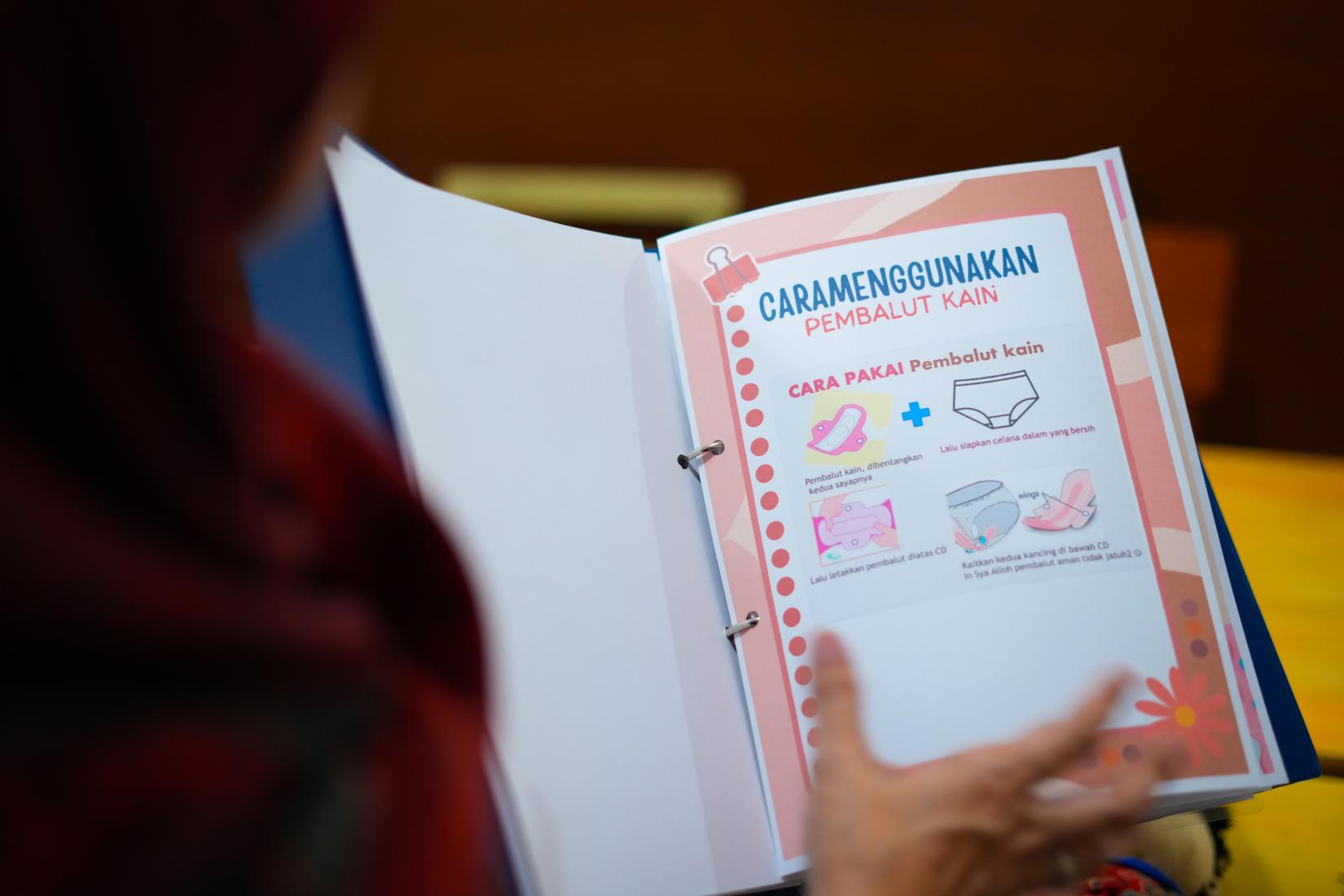

Learning materials Ms. Gusnaeni adopted or developed after attending the UNFPA-Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology course include anatomically correct dolls, and annotated aprons teachers can wear that illustrate the male and female reproductive organs. She also created a tactile book that helps students with intellectual disabilities learn to manage their periods. On successive pages, soft felt pouches contain products such as sanitary towels, tampons, and menstrual cups.

More than a third of girls (38%) who have started their periods feel ashamed of their bodies during menstruation according to Indonesia’s 2019 Global Early Adolescent Survey, with 8% reporting that they do not feel comfortable discussing menstruation. For students whose intellectual disabilities that cause gaps between physical development and cognitive abilities, self care can be even more difficult. These gaps also coincide with a heightened risk of exploitation. Research conducted by the University of Liverpool and the World Health Organization (WHO) across 17 low-income countries shows that children with disabilities are 2.9 times more likely to experience sexual violence or harassment compared to their peers without disabilities, while children with intellectual disabilities are 4.6 times more likely.

“Every young person, without exception, has the right to reproductive health education so that they are well equipped to protect themselves from challenges that adolescence brings, and make informed decisions about their body and future,” says Anjali Sen, UNFPA Indonesia Representative. “It is even more critical to provide Adolescent Reproductive Health education for adolescents with intellectual disabilities who are more vulnerable to exploitation and sexual abuse.”

Providing education on the emotional, physical, and social aspects of sexuality to adolescents with intellectual disabilities is a core component of a UNFPA pilot programme that aims to enhance teachers’ adolescent reproductive health education skills. Besides West Java, where SLB-C Plus Asih Manunggal is located, the 2020–2025 pilot operates in Aceh, North Sumatra, Banten, Central Java, East Java, Bali, Central Sulawesi, West Nusa Tenggara, and Papua. It has trained 332 “master teachers” to date, who have in turn familiarized a further 1,158 teachers at junior high school and 694 teachers at special needs schools with the curriculum, reaching 14,712 junior high school students and 246 students with disabilities.

SLB-C Plus Asih Manunggal headteacher Wiwin Wiartini, 59, says that in the past, she had reservations about whether sexual and reproductive health education was appropriate for the school. Some parents felt uneasy about the subject and teachers considered it “vulgar to use correct anatomical terms such as penis and vagina.”

A turning point came when a 19-year-old former student became pregnant after having been sexually exploited by a neighbour in 2020. The incident underscored the importance of teaching students about boundaries and consent, says Ms. Wiartini. Attitudes also began to change when parents and teachers observed students like Nabila, Kanza, Lazuardi, Cici, and Jenar becoming more confident, expressive, and autonomous.

Once a controversial subject, sexual and reproductive health education is now the leading programme at SLB-C Asih Manunggal, which collaborates with a local university on pedagogy. As a “master teacher,” Ms. Gusnaeni has taught her methods to teachers at 20 other schools across West Java, observing their lessons and developing best practices based on the approaches that prove most effective.

“We really learned from this experience,” says headteacher Wiartini. “Since implementing this programme we understand its importance and we want it to be nationwide.”